The death of Magnus Olafsson in 1265 terminated for a long period the democratic freedom of the Manx people, a freedom which they had enjoyed for over three hundred years. Their Norse ancestors had raised the Isle of Man as well as islands of the Hebrides to a position which is almost unique in history; they had made them a power, but the greater kingdoms around had become covetous and planned for the opportunity to possess them.

Jealousies eventually arose between the Kings and the courts of England and Scotland. They were feuded monarchs, and were envious of any smaller and independent nations around. Aggression was then the key-note of both the feudal courts of England and Scotland, and Man had to suffer for a century both the predatory invasions from Scotland and the cruel impositions of England.

The death of Alexander III of Scotland in 1285 introduced a new era. Bruce and Baliol both claimed the Scottish throne, and Edward I of England was invited to decide between them. In 1292 he fixed on Baliol, giving him paramountcy over Man, and reserving his own rights as Lord Paramount. Thus, through the influence of the English monarch, Man was again reduced to subjection. Disputes between Edward and Baliol ended in the imprisonment of the latter.

In 1298, Antony Bek, the warlike Bishop of Durham, being then a favourite of King Edward I, was put into possession.

Man had now no military power and Edward had no compunction about taking full advantage of this. Bek was a fierce prelate, and is said to have gone to fight the Scots at the head of 120 knights, 500 horse, and a thousand foot, and there were no fewer than twenty-six standard bearers of his own kin.

In 1313 Robert Bruce was made king of Scotland, and in the same year he cast his covetous eyes southwards to Man. He invaded it with a large fleet. Our Chronicle, in one of its final pages, says he put in at Ramsey, and on the following Sunday went ‘ad Moniales de Dufglas’, (which has been translated ‘ the Nunnery at Douglas,’) where he spent the night.

On the Monday he laid siege to the Castle of Rushen, which was defended by the Lord Dungali Mac Dowyle until the Tuesday after the Feast of St. Barnabas (June 21st) on which day Bruce took the castle. Thomas Randolph, one of his henchmen, was given charge of the Island.

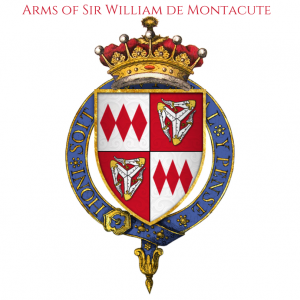

Prior to Bek’s death in 1310, there had been in the field for the throne of Man, two notable claimants. In July, 1291, Lady Mary, daughter of Reginald II, King of Man, did homage to Edward I at Perth. The other claimant was Aufrica, daughter of Olav the Black and a sister and heiress of Magnus the last King of Man. The union of the two claims in the person of Sir Willam Montacute – who was a descendant of both ladies – simplified the problem, and eventually Edward made the grant to him.

Sir William Montacute, who was in power from 1344 to 1393, sold his kingdom ‘with the title of being crowned with a golden crown’ to Sir William le Scrope, Earl of Wiltshire, for, according to Capgrave, ‘he that is lord of this yle may were a crowne.’

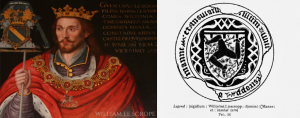

He continued in power to 1399, when he was beheaded by Henry IV for having taken King Richard’s side in the civil war. There is a portrait of Scrope, done in the time of Elizabeth, so it is said, showing him wearing a golden crown.

Sir William le Scrope, in 1396, was one of the signatories to a treaty of peace, to last for twenty-eight years, made between France and England on the marriage of Richard II of England and Isabel of France. He signed the ordinance as one of the allies of the English King, and pour la Seignourie de Man. The original seal is in Paris appended to the document. There is an engraving of the cast of the seal, which is in the British Museum (see photograph).

Scottish and English jealousies had their repercussion on the Island, and the seas around were frequently the scenes of bitter struggles. But after 1346 conditions became more settled, for the English, now under Edward III, dealt the Scots a decisive blow at the battle of Neville’s Cross, and they assumed arbitrary power over Man from that time onwards.

After Scrope’s death, all opposing claims having expired, King Henry granted the Island to Henry de Percy, Earl of Northumberland, subject to the service of carrying, ‘on the coronation days of us and our heirs,’ the sword called the ‘ Lancaster sword.’

In 1403, the Percys rebelled, and were defeated at the battle of Shrewsbury, and King Henry, in the following year gave the Island, ‘with its castles and royalties and with the patronage of the bishopric,’ to Sir John Stanley, his heirs and assigns, ‘on the service of rendering two falcons on paying homage, and two falcons to all future kings of England on the day of their coronation.’

The most distinguished lawyer who ever sat in Tynwald – and he had his place for thirty-nine long years – was Sir James Gell. Whatever he wrote in the sphere of law, history, or custom, was always accepted, and there was more than one occasion when he confounded the English Attorney-General and Solicitor-General in their reading of the law affecting the relations between England and Man, and particularly in the instance of their attitude as to the power of the Tynwald to pass an Act for the re-arranging of the revenue of the See of Sodor and Man. He comments :

‘The ancient laws and constitution of the Isle of Man have continued from the earliest time of which there is any account, without any change having been effected by any conqueror of the country. In the various and frequent changes in the sovereignty from the time of our own King Magnus in 1265, there is no instance known (historically or otherwise) of any change in the law or constitution having been ordained by any person who may have been in a position of a conqueror, until the time of the interfering Revesting Act of 1765. During all that long period appeared no loveable or popular ruler, or even a sympathetic one, to whom the people of the nation could bind their hearts.’

‘In 1765,‘ says Sir James in cold legal phraseology, ‘the rule of the feudatory sovereigns ceased, and the direct rule of the Sovereigns of England commenced; the sovereign rights of the feudatory sovereign merged in those of the Sovereign paramount; but otherwise no change took place in the government of the Island as a separate Kingdom.’

(source: Island Heritage by William Cubbon (1951); photographs: Arms of William de Montacute http://bit.ly/1lhkfI2; William le Scrope http://bit.ly/1NOJuZn; Robert the Bruce http://bit.ly/1YtDYD8; Henry Percy http://bit.ly/1PYuNaG; Arms of Sir John Stanley)