A Descendant of the British Prehistoric Horse…

“The Manx breed (of horses) are low and little…A reasonable tall man needs no stirrups to ascend him; but, being mounted, no man need to desire a better travelling beast.” ~ Blundell, 1648.

“Formerly the ponies were remarkable for their beauty and were much in request in England and Ireland to run in carriages; but now their numbers are much diminished as larger horses are found more useful.” ~ John Feltham, 1798.

“The Island had formerly its peculiar breed also of ponies, fine boned, sure footed, blacks, greys and bays; from neglect this breed also has become nearly extinct.” ~ Thomas Quayle, 1812.

“The small breed of horses, for which the Manks in common with the Out Isles were once famous, is now almost extinct.” ~ HA Bullock, 1816.

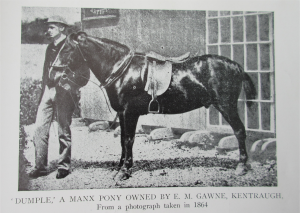

The last of the Manx Ponies are remembered by a few people still living and references like those above may be found in books about the Island written during the past three hundred years. It is therefore a little surprising that this interesting representative of the ‘Celtic Pony’ seems to have escaped notice in all published accounts of the horses of the British Isles. Now the unexpected discovery of two actual photographs of one of the last of the ponies – after several years of fruitless searching for any sort of picture of the breed – provides an opportunity to summarise what is known of the animal.

The origin of the True (or Domesticated) Horse and the ancestry of modern breeds is not yet fully unravelled, but three independent groups are generally recognised:

1) The oriental light-legged group (e.g. the Arab) which originated on the plains of central Asia and reached the Near East about 2000 BCE

2) A heavily-built forest type separately domesticated in Europe (e.g. the old Flemish breed); and there were also

3) the native, or Celtic Ponies of the British Isles, with which we are here concerned.

Selections and mixing of the groups during historic times produced many breeds adapted to the various needs of mankind: for warfare, for transport, for agriculture and sometimes for food. As one instance, the old English Great Horse (now represented by the Shire) was bred from the native pony and the larger Flemish horse. But the Celtic pony, well suited to the moors and hilly country of the north and west, survived in the highland regions of Britain. In the course of centuries these native ponies became differentiated into slightly different types by inbreeding and sometimes by crossing to increase their size.

Of these types the Shetland is the best known and also the smallest – not more than 10½ hands. The Highland or Galloway ponies are large on the Scottish mainland (about 13 to 14 hands in height), where they are used for farm work, while a lighter form is employed as a pack horse by the Hebridean crofters. In Wales the mountain pony averages 11 or 12 hands, while larger types occur on the lowland farms. In the north of England very sturdy and rather heavily-built breeds (12 to 14 hands) still survive in the fells of Cumberland and Westmorland and in the Yorkshire Dales. Others survive in the south on Darmoor, Exmoor and in the New Forst, but like nearly all the descendants of the Celtic Pony, their numbers are diminishing since they are no longer required for haulage in the mines. In Ireland also, a similar form is still bred extensively, especially in Connemara, and excavations prove that the same type was already well established in that country by the close of the Bronze Age. The Iceland pony is also a member of the Celtic family and may have been introduced by Viking settlers from these Isles.

As the Manx pony is now extinct, its appearance can only be judged from pictures which happen to survive, from written descriptions, or skeletal remains found in the course of excavations. Of the latter only one example is known so far: the skeleton of an early Manx pony discovered in the Viking ship-burial at Knock y Doonee, dating from the year 900 CE or thereabouts. It is an interesting point that the ornamentation of the bronze harness-mounts found with this pony was of local design (that is Celtic rather than Norwegian). Although such ponies are figured on several Manx crosses carved about 1000 CE, the style is conventionalised and the only accurate pictorial records seem to be the photographs found last year in a mid-Victorian album in a Buckinghamshire country home.

When the late Mrs Roscoe (née Gawne) of Horn Hill Court, realised the interest to these unique photographs she at once despatched them to the Museum with her comments in a covering letter to Mr Cubbon:

“This afternoon Mr Megaw looking through an old album of mine is much impressed with the photo of our Kentraugh Manx pony, taken in 1864. My father, EM Gawne, bought this pony in 1852 or 1853 from Mr Edward Farrant’s from the north part of the Island as about the best and last specimen bred of the old Manx stock. ‘Dumple’ was a very dark chestnut with a white stripe down frontal, mouth of iron, lazy in the shafts but a regular run-away in girls’ hands riding – I expect he had never been properly trained.” ~ (signed) Kathleen E Roscoe, 13 March 1942

The vivid first-hand record by ‘Dumple’s’ owner shows that the photograph can indeed be accepted for what their hand-written titles declare them to be, namely, pictures of a Manx pony taken nearly 80 years ago. Mrs Roscoe passed away a few days after penning these lines and with her, her rich store of memories of Manx life in the 19th century.

The photograph shows a well-groomed example of the horse which was an indispensible feature of the Manx countryside for many centuries, without doubt from prehistoric times until little over a hundred years ago. Such ponies were chief means of travelling, for until the close of the 18th century, roads were unfavourable to any means of progression other than horse-back, and everyone knew how to ride. English travellers sometimes indulged in sarcastic allusions to the inferior size of the unkempt appearance of the Manx ponies; yet they were always ready to admit the sterling qualities of the ‘poor nags’ – as well they might, since their sight-seeing would have been impossible without them. Three hundred years ago William Blundell, a Lancashire Cavalier, declared that:

“They will plod freely and willingly with a soft and round amble, setting as easy as your Irish hobbies; you have no need of spurs or switch. In enduring labour and hardness they exceed others, they will travail the whole day and night also, if they be put to it, without either meat or drink.”

But the rest of the description is less complimentary and, like many travellers’ tales, is probably somewhat exaggerated for effect:

“The Manks breed are low and little, equal with the least of the above named (except the merlin), and withal frightfully poor, and the most insightly that may any where be found…You are scarce able to discover any head for hair, which is of a sooty black colour: I could not discern any of them yet had so much as one white spot in foot or face, nor other colour but the chimeria black in any part of their body. This long scaring stragling hair hangs dangling down almost 2 or 3 handfuls beneath the whole length of their bellies, their excoriated hides are not (by the bye) to be distinguished from a bear’s skin.”

The excellence, as well as the quaintness of the Manx ponies became well-known outside the Island. Feltham’s statement that they ‘were remarkable for their beauty and were much in request in England and Ireland to run in carriages’ is borne out by a series of letters addressed by a Dublin man to William Crebbin, a leading Douglas merchant, in the year 1778. The Dubliner writes:

“A friend of mine has requested me to write for one of your little horses, about 2 Gs and a half price (two and a half guineas), not too small; and another begs to have sent him one of about 13 hands, strong and round if such can be got. I know you have judgement in these matters.”

The next letter from Dublin announces that:

“The Mx ponies came safe and am obliged by your sending them. They are liked by the Gentleman for whom I got them and shall pay your Order whenever sent. I shall trouble you to get me two more for a friend again next spring. They are for a lady whom I have particular regard for, and would therefore wish to have them handsom. They must be mares with their full tales, about 4 or 5 years old. They are intended for a Phaeton and should be an exact match and of a strong kind. If cream colours could be got the better. I shall once more request your being particular and as she will not want them sooner than May, you will have time to make inquiry for me. Let them be tall as you can get. You will pardon this trouble and in turn command me etc…”

From this correspondence it may be assumed that ‘about 13 hands’ was considered a good size for a Manx pony. The usual colour of the ponies is not revealed but we have seen that Thomas Quayle, the agriculturalist, describes them as ‘blacks, greys and bays’ which recalls a contemporary description of the Highland pony.

Apart from the service rendered by the ponies in carrying their masters from place to place, they were invaluable beasts of burden. Naturally in a hilly country, transport was difficult and carts were out of the question without good roads. The simplest methods were best and the pack pony, and sometimes the wheelless ‘car-sleod’ were the normal means of carrying hay and oats from the fields, turf from the mountains, and stone and timber for building.

Some are said to have carried loads of as much as a quarter of a ton of lime in panniers from the quarries in the south to the northern farms, a distance of some thirty miles over night after travelling down to the quarries the day before.

Besides the arduous duties already mentioned, the ponies were also expected to do the ploughing. Nevertheless Quayle records that in the uplands where the ‘small breed of horses is yet to be found’ (in 1811 when he wrote his treatise) they were ‘kept at slender expense and rarely housed in winter’:

“When wanted they are fetched home in the morning and after a feed of sheaf-oats or hay, worked all day, and in the evening, after another feed, dismissed again to the pasture (i.e. to the mountain common).

The animal thus treated must be unequal to the spring-ploughing; but from the cessation of work in summer, gradually recovers. Since the complete establishment of two-horse ploughs it has become necessary that the husbandry-horses should possess strength…

When hard pressed for food in winter and spring months, horses in rough pasture are said to have found out the means of procurring food from furze. They attack the growing bush with their fore-feet and, with the aid of their shoes, are enabled to pound it till it can safely be masticated.”

Gradually they disappeared even from the country fairs at which they had been one of the great attractions. Receiver-General Quirk remembered them at Periwinkle Fair held near the Poolvaash shore:

“The chief articles of trade brought forward to attract visitors, as far as I then knew, were periwinkles and ginger-bread. They were also on show cattle and most particularly, ponies of the ancient breed. The fair has not been held for forty years past – that is since about 1820.”

After that date there are few printed references to the ponies as a living breed. A guide book of the 1840s mentions that they were then used to carry visitors up the Maughold lhergies to the summit of Snaefell. A few of the old stock were deliberately preserved by individual farmers in the locality who realised their commercial value. At Ballajora lived Paddy Lowey who was remembered until recently as a great breeder of Manx ponies. It was from Lowey that the late Mr Edward Farrant, of Ballakillingan, acquired the famous ‘Blackbird.’ As already mentioned ’Dumple’ was purchased from Mr Farrant about 1852, so he probably originated from Ballajora also.

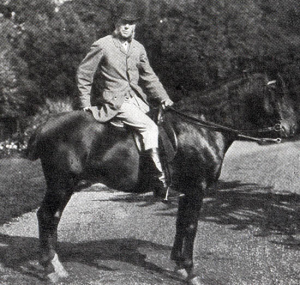

‘Blackbird’ is the last of the Manx breed of which we have any reliable information – and even this is not so reliable as one could wish. While a local man who knew Lowey maintained that ‘Blackbird’ was a pure-bred Manx pony, it is sometimes said that he owed his acrobatic skill to an Arab parent and not to his Manx mother. Without a photograph of the pony it is impossible to decide whether this aspersion on his ancestry is justified or merely a legend which (as often happens) gained currency because it seemed to explain the remarkable qualities of the creature. Rev. Edward Paton, who remembers the pony in the 1870s writes:

“I remember ‘Blackbird’ very well. He belonged to Edward Farrant, who always rode him. He was a famous jumper and used always to win the prizes at competitions at the Agricultural Shows, not only in the Island but on the mainland where he was cheered as ‘the little Manxman.’ Christian of Lewaigue, and also Bobby Dawson, used to ride him in these competitions.”

So after centuries of worthy and arduous toil in the service of his masters, the ‘little Manxman’ vanished quietly from the native scene. Now hardly a soul remembers him.

The Manx Pony is no more, and this Island is the poorer for his loss.

(source: article written by BRS Megaw and photograph of ‘Dumple’ from The Journal of the Manx Museum Vol. V, No.68 (1943); photograph of Edward Farrant (?) and Blackbird (?) from Ballaugh Heritage Trust where there is also a short article on The Manx Pony)